Are lemons fast or slow?

Did you say fast? I did, and apparently so do most people. Though I’ve personally never seen a lemon get up and run (if you have, please get in touch with me; I’m intrigued), the answer seems strangely instinctive.

Asking me this question is Dr. Tereza Stehlíková, an artist, filmmaker, and head of the Visual Arts Department at the University of Creative Communication, Prague. We’re chatting over Zoom about her work, much of which focuses on the interaction of our different senses, and how that interaction can give meaning to our human experience. Her current exhibition, Ophelia in Exile, reflects on this idea. It explores how the COVID-19 pandemic, especially the necessary but endless screen usage, has accelerated a shift toward a virtualized, flattened reality.

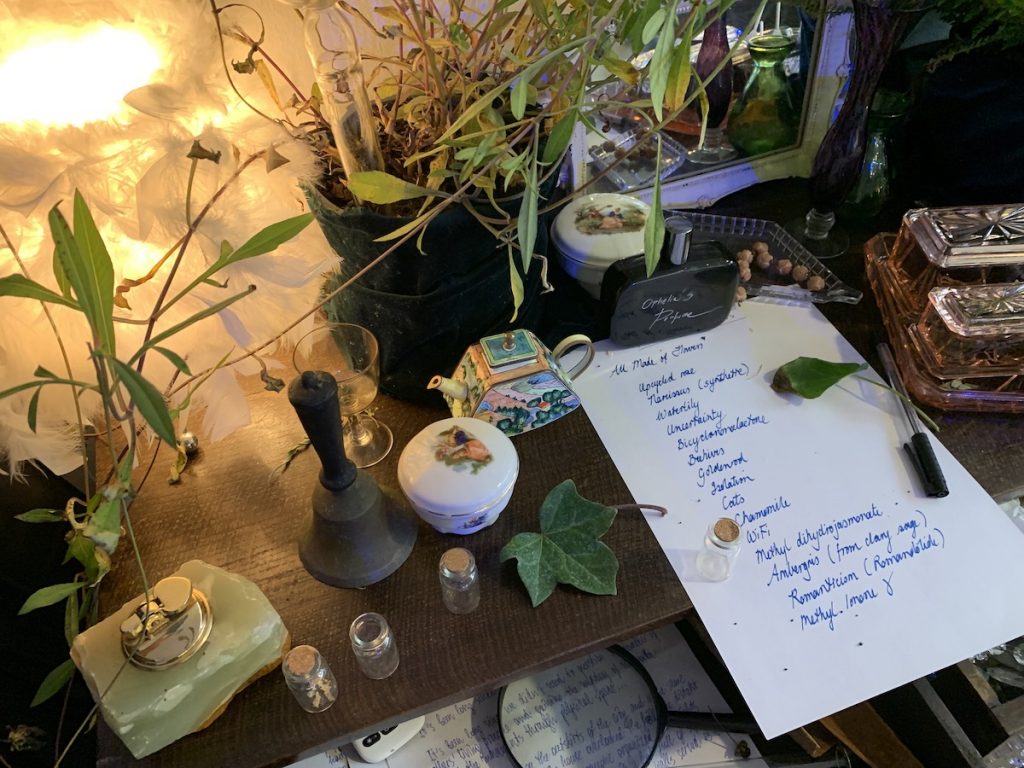

Ophelia in Exile launched in October 2021 and will run until the end of February 2022 at the Czech Centre’s Vitrínka Gallery, in London, England. It’s the product of a collaboration with Tangible Territory Journal, of which Stehlíková is editor.

The exhibition proposes that Ophelia, the literary character, has been quarantined in an unknown location for an unknown period of time. Though she’s filled her living space with sensory remnants of nature—herbs, flowers, vines—her only means of engagement with the outside world is through screens. The exhibition invites you into Ophelia’s living room, the location of her “sensory exile,” as Stehlíková puts it. Though you won’t meet Ophelia in person, you may spot her in the screens throughout the space. You can leave her notes, letters, and gifts, but if you can’t make it to the exhibit, you can email Ophelia a message of support (opheliainexile@gmail.com) or even follow her on Instagram.

Stehlíková has long been interested in the sense of touch and creating multisensory experiences. Her PhD at the Royal College of Art examined how tactility can be evoked through audio and visual means. As she finished her PhD, she began connecting with scientists studying the senses, expanding her focus to smell and taste. “I like this idea of this sort of contradiction, almost—how can audiovisual mediums communicate smell?” Stehlíková explains.

She connected with Dr. Charles Spence, head of the Crossmodal Research Laboratory at the University of Oxford, who studies how the brain processes information from each of our senses to form the experiences of our daily lives. This phenomenon is not synesthesia, but rather the nuanced ways the senses interact with one another. Dr. Spence works with advertising agencies to figure out how someone might, for example, hear the taste of whiskey. Apparently, there is a level of consensus about which sounds are associated with what sort of taste, with some sounds associated with sweetness versus sourness. This is where the speedy lemon question comes up—there seems to be a general agreement about the correlation between a sharpness of taste and speed.

The senses are also connected to emotion and memory. Stehlíková tells me about a sensory workshop she ran, in which she blindfolded participants and asked them to smell and touch various materials in a box—sand, moss, dried lime, herbs, etc. She asked participants to write any associations the materials prompted. “They actually trigger some amazingly emotional responses in people,” Stehlíková tells me. “There’s a lot of childhood memories that get triggered by smells and touch, especially if you take away sight.”

So what happens when these components of our lives are lost? Enter Ophelia, who has appeared in Stehlíková’s work before, for example, drowning in a soup bowl. In this exhibition, she serves as an alter ego for the artist, reflecting Stehlíková’s own feelings of flatness and disembodiment during quarantine as the world was reduced to screens. “Connected very much is this feeling that I had during the pandemic that…our rich multi-sensory world has been taken away from us,” Stehlíková tells me. “At the time, I also launched…Tangible Territory, and I started to invite people, artists and philosophers, to reflect on this idea of what’s happening. We entered this virtual reality that’s already been happening, of course, but now it just got much more heightened.”

She thinks that this flattening of our lives through the increased use of technology has been happening for a while, but the pandemic has accelerated the trend. “So again, this was the idea that we are spending so much time looking into screens, now that’s the window into the world,” Stehlíková says. It’s made her appreciate non-digital experiences even more—going into a physical store, the commute on a train to a film screening. She explains that she “already had this sense of grief…for something that’s been taken away from us. And of course, it’s better now. But still, something’s transformed.” She muses, “I started thinking about this idea of sensory exile, like exile from the origin of the senses, and how that would feel.”

With Ophelia in Exile, Stehlíková hopes to capture something as it’s transforming, this transition of an old reality to a new one. “So that it’s not just happening, that we actually really figure out what’s important, and what we want to lose and what we don’t want to lose…basically trying to process what’s going on and think about it,” Stehlíková explains.

Ophelia in Exile is a work in progress, that Stehlíková hopes to develop it in tandem with the ever-evolving state of the world. For example, Ophelia’s living room might move to different countries, when conditions allow. “But also, maybe the meaning will shift,” Stehlíková adds, “or it will develop, depending on how the situation’s developing. I think it’s kind of an ongoing project. That’s what I want to say—it’s definitely not finished. Because I think it’s still very relevant, and it will keep being relevant.”