Name: Mesa Schumacher

Which came first in your life, the science or the art?

I’ve always loved science and art and, growing up, sought both out. I painted and sold furniture and taught ceramics, but I also worked as a teen naturalist/interpretive volunteer for the Seattle Aquarium.

When it came time to pick a path, I chose science, probably because I had stronger mentorship in that area, and I felt like art was not a very practical choice. Everyone I knew who was pursuing art seemed to have a strong sense of identity or social theme to express, and I didn’t feel like that was something I connected with strongly. I liked to interpret what I saw and learned, and work out ideas with my art.

However, once I got to university, I started bio core and my premed requirements, and I realized that my heart wasn’t in pursuit of a medical or a PhD path. I think at heart I am more of a communicator and synthesizer than an experimenter. I liked taking part in the practice of science, but it is the task of visualizing it that runs through my head at night, not assay design. I probably would have had a very happy career in medicine or research, but I think I probably fit best where I landed.

Luckily I discovered the practice of scientific illustration, and it felt like a perfect fit for my interests. Despite the well-meaning advice of many, I refocused my energy on becoming an illustrator, and over time I have come to think of myself more broadly as an artist and scientific visual communicator and storyteller. However, I am very happy I have had the chance to experience both sides.

Which sciences relate to your art practice?

I began my work in archaeological illustration, which is a fascinating niche, but I hardly get to do any work there anymore!

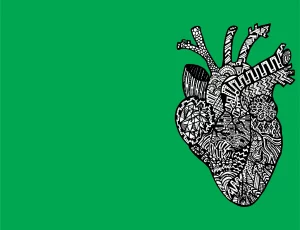

I completed the Biological and Medical Illustration program at Johns Hopkins and am a certified medical illustrator, so I do a lot of work with medicine, and I love it! Medical visualization has some of the most interesting and complex ideas to try and convey visually, and arguably some of the hardest-hitting human impacts and need to do so.

However, I also love biological sciences, and much of my personal and professional work also veer there.

I work often with National Geographic, helping design and execute infographic spreads, and generally, my stories are biologically themed. This year I’ve been exploring biodiversity in a daily animal series that has been pushing my digital painting skills and really enjoyable positive online engagement during a pretty antisocial time for many, myself included. Biodiversity is so vitally important, and I think most people don’t appreciate the insane range of life and biological strategies that are out there—for some reason we skip the most interesting stuff in school. It has been really fun to share my interest in biology each day this year.

What materials do you use to create your artworks?

I began getting serious about my traditional and digital training at about the same time, so I grew as an artist with one foot digital and one traditional. I’ve moved around a lot in the past decade for my partner’s work, living in Guatemala, Nepal, and just moved again, this time to Fiji. I find I do most of my work digitally these days, though I still do the scan in traditional prints and textures to add some organic-ness to my work. I generally gravitate to art with a bit of chaos and don’t like my art to be completely polished. I like to use whatever technique best suits what I am working on—that is one of the great joys of being a science artist—I don’t think anyone expects me to produce art that is always in one style. I get to experiment more and use what works. Sometimes it is best to start in 3D and then go more painterly, other times I try to approximate traditional techniques like pen and ink or watercolour. I am always excited to learn and incorporate new tricks into my toolkit.

Artwork/Exhibition you are most proud of:

I am often most proud of whatever work is currently capturing my attention, as in scientific visualization, each is a bit of a rabbit hole I need to go down. There is research and learning involved, then processing, output, and revision.

I am quite proud of some of the editorial work I’ve done for National Geographic and Scientific American, as I love distilling topics down to a level where any adult can learn about them and find some wonder in science.

I am also very proud recently of the puzzles I’m working on with Genius Games—we made a ten-foot-tall, seven-piece anatomic human, a true puzzler’s challenge. It is pretty fun to try and reconstruct my own work.

This year, of course, I have been completing an animal illustration a day, which I post online, to share a bit of learning and positivity during a horrible year. I am very proud of the 300+ images thus far created and some of the compilation compositions I’ve been working on with these animals. It has been such an inspiring outlet for me over the course of the year, and I hope to keep up the same drive in my personal art in the coming years. I haven’t shown very much in recent years due to the energy it would take away from my freelance work and my constant moves, but would like to return to showing in the coming years. We’ll see where things go!

Which scientists and/or artists inspire and/or have influenced you?

I’ve been influenced by so many scientists and artists it is impossible to name them all here. I am influenced every day by my scientific clients, who collaborate with me to build visuals of their ideas. For those who haven’t worked with a scientific illustrator, the process is very collaborative! Clients bring research, ideas, or conceptual problems to me, and we work together to find the best way to communicate the necessary information to their audience. This means evaluating what goes in and what needs to be simplified to best convey important concepts, and what style or medium might best tell a story.

I’m a little addicted to the process actually, so I’ll probably never retire, even if I move into different areas of art. In my art, I draw a lot of inspiration from classical science illustration, traditional painters, and lately printmaking. My work of course draws from my study at Johns Hopkins and all the fantastic faculty of medical illustrators there, and from the infographic artists at National Geographic, notably Fernando Baptista with whom I worked as a young artist, and who taught me a lot about design and practice.

SciArt is an emerging term related to combining art and science. How would you define it?

I love the SciArt tag, as it covers so much and speaks to what I think science art is becoming—celebration and communication of science. I love the traditions of conventional and detailed scientific illustration, but love that comics, more expressive works, and conceptual visualizations are making their way into the fold as legitimate and important art forms.

I’d define SciArt as art or visualizations that seek to increase understanding and appreciation for scientific processes and ideas. This can mean visualizing an incredibly complex mechanism of action in your body, a surgery, ecosystem, or how the theoretical theories.

I love that this term leaves space for incorporation of data visualization, interactive experience, bio-art…the list goes on. We aren’t just talking illustration or animation. The more space we can make in this field for different actors and collaborators the better. There is lots of room in this space, and we need more active members!